If I showed you a beer stein, most likely, you would know what culture is represented by it. You would look at it and gather from what you’ve seen in mainstream American culture what it is to celebrate German heritage.

You’ve at least heard of Oktoberfest celebrations, got news of the White House acknowledging German-American Day on October 6th every year, and have seen the traditional Bavarian dress worn at festivals.

I grew up in the Midwest hearing of Oktoberfest celebrations with people dancing in lederhosen and dirndl while balancing pints of German beer.

Having some German heritage, I admire these festivals’ dedication to keeping the German-American culture alive in the Midwest, especially when you consider the history of the German language taking a massive hit during times of war.

The language became lost to the German-Americans, so their descendants speak English but deeply love their culture.

Of course, they throw in German words here and there, but they don’t rely on language alone to express their culture. Instead, they heavily rely on visual culture with traditional dress, dancing, music, food, and beer.

Along with Oktoberfest, the festival of Maifest also welcomes visitors to a springtime celebration. Because it’s a German-American tradition, the Maipole dancers wear the Bavarian dress adorned with flowers.

They know the visuals that symbolize them as a culture and roll with it, despite not speaking fluent German. People from all over visit these celebrations and enjoy embracing the German-American culture.

Another prominent cultural group I admire in the Midwest is the Dutch, specifically the town of Pella, Iowa. I’ve enjoyed walking the streets decked out with traditional Dutch architecture, complete with a large windmill overlooking the town square.

Within the central area, you’ll find gardens of tulips with statues of a man riding his bike, a woman holding tulips, and children playfully running. Handpainted murals of Dutch culture greet you throughout the town as you explore.

Every spring, they hold their annual Tulip Time festival, dedicated to the profoundly Dutch heritage of the town. The children learn traditional Dutch music and dance in public school, which they perform every year for the crowds during the festival.

Speaking fluent Dutch isn’t called for in this celebration. They proudly lean into their symbolism of tulips, windmills, the traditional Dutch dress, their ritual of scrubbing the streets before the festival parade, and fresh-baked Dutch treats.

When I want to describe the symbols of Franco-Americans, I get stuck on what there is to show. Of course, we have the fleur-de-lys, unique musical traditions of our own, and traditional French-Canadian recipes. Still, I never see anything as concrete as other cultures around us at the forefront.

Often, our invitation is a question of whether we speak French or not. If we only speak English, we are told that we cannot understand ourselves and are doomed to die out.

Previously, the closest things to physical Franco-American symbols were symbols of Catholicism. From crucifixes and Virgin Mary figures found in the home to rosaries found within coat pockets and purses, religious symbolism was the visual culture.

When I visited the area of Sainte-Marie’s Parish in Manchester, New Hampshire it seemed as though the church is only remembered as a historical site of days gone by rather than strong symbolism representing Franco-Americans of today. Walking to Lafayette Park with the statue of Ferdinand Gagnon, it looked as if the area had seen better days.

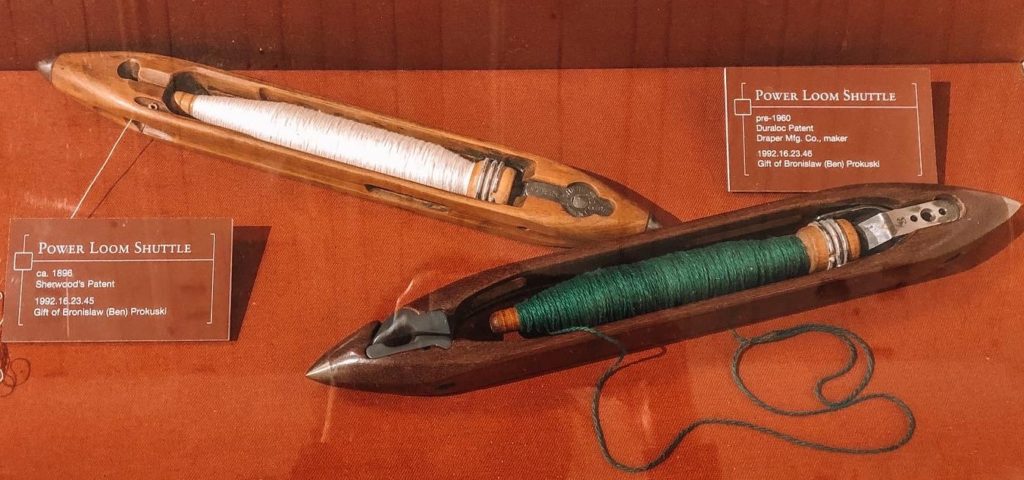

Exploring more of our history, I visited the Millyard Museum in Manchester. Among the exhibits, I learned the mechanics of the looms that many French-Canadian immigrants worked on in the Amoskeag Mills.

In another section below the screening of an old documentary was a long glass display case holding various objects. While I admired the cultural artifacts, I couldn’t help but notice that there was nothing to showcase the French-Canadian culture in representing the groups who had contributed to work in the mills.

There was a flower headdress and a vest worn by young Polish girls, traditional Greek dancing shoes, a Jewish prayer shawl, and juggling batons from German and Belgian immigrants.

But nothing from the French-Canadians, as if they had nothing cultural to give this display. Not even symbols of Catholicism. Although these objects were donations, it was odd not to see a piece of Franco-America beyond the glass.

Franco-Americans throughout New England, and the Northeast as a whole, have rich musical talent, French language skills, and deep roots in the Catholic faith. But these aspects of our culture haven’t remained in all of us.

As Franco-Americans, we have a distinct culture whether we speak French or not. We have our own history and presence that is separate from French-Canada. Because of this, I would like to propose that we expand on claiming certain symbols for ourselves that represent us as a group and a culture in the United States.

Of course, we are of French-Canada in terms of ancestry, but I believe that some of their symbolism doesn’t represent specific references to Franco-America. We should embrace the traditional French-Canadian music and Podorythmie, folklore like La Chasse-galerie, French-Canadian cultural festivals, and whichever other aspects we choose for ourselves.

Not all French-Canadians are Franco-Americans, but all Franco-Americans are descended from French-Canadians.

We can take inspiration and cultural identity from our French-Canadian past and apply it to our Franco-American future. We can celebrate our “Old World” culture with the addition of new symbolism that specifically speaks to us.

Having a cultural identity in the visual arts is crucial to cultural connection, especially within its own group. Language is not the last thread preventing a culture from falling apart.

So, in establishing new symbolism for ourselves, objects that I think would be excellent symbols for Franco-Americans, and ones that I have not seen anyone else claim are the shuttles and bobbins of the mills. Yet, I’ve seen these referenced before at a Franco-American presentation and described in Franco-American music with a song titled “The Shuttle.”

We left our home in St. Hubert to work the Amoskeag

In Manchester, New Hampshire, in 1883.

Six days a week we rise at four to work our sixteen hours.

Ma mère and me are spinners inside their tall brick towers;

Mon père, he’s in the weaving room; mes frères, they sweep the floor.

We see them, but we cannot speak above the shuttle’s roar.

Chanterelle, the shuttle

The song describes the exploitation Franco-Americans faced working in the mills, but there is something to be said about the power of their resilience. It speaks to us as their descendants who still hold their surnames in our family tree. When we recognize the many other French-Canadian names found on street signs and businesses, it’s as if the long-gone voices behind those names greet us for a brief moment in the present.

To diminish the shuttles and bobbins as tools that harmed our Franco-American ancestors wouldn’t be telling the whole story. We can’t imagine how demanding that workload was at the time; we can only picture it from the stories passed down to us by our older family members who lived it. I believe the shuttle is a vessel that keeps these memories alive for us as a group to remember and honor.

La Dame de Notre Renaissance Française in Nashua, New Hampshire is a statue of a woman and her son. They represent the French-Canadian immigrants who worked in the New England mills, more specifically, as a remembrance of the women and children in the mills.

In the pocket of her dress, La Dame holds a different mill tool. Instead of a shuttle with a bobbin, she has a spindle, which spun fibers into thread by hand.

The statue’s artist says the spindle symbolizes the work done in the mills by many women and their children. As reflected in this statue, these tools hold meaning for us through history and culture.

These were simple objects used for strenuous labor in the mills, but they are more than a simple relic of our past. La Dame holds her mill tool closely, so why don’t we? Rather than viewing them as objects of the past, they have the potential to become symbols of strength and resilience.

Ma mère grew up in Nashua in what was at the time a primarily Franco-American neighborhood. In response to the idea of making the shuttle a symbol, she told me that when she was in school at Holy Infant Jesus, the nuns gave the kids bobbins to use as rhythm sticks in music class.

It may seem insignificant, but I find a connection with my mother once holding the bobbins in her music classes when Franco-Americans before her loaded those bobbins into the shuttles during their demanding shifts toiling away in the mills.

These shuttles, bobbins, and spindles symbolize us: they’re durable and have withstood the test of time. There have to be thousands of them hidden away, disregarded as outdated mill tools waiting to see the light again.

It’s never too late to recreate symbols of our culture and clear a path forward which allows us to express Franco-America in new ways.

Rebecca Drew

Thank you for saying that “Language is not the last thread preventing a culture from falling apart.” Beautifully said. I am not a member of the “Franco-American” community despite having some French Canadian ancestors, so I don’t want to offend anyone by offering suggestions for symbols. However, the warmth and acceptance conveyed by other groups can go a long way to keeping a culture alive. For example, Irish-Americans don’t tell the non-Irish to stay away from St. Patrick’s Day parades. Like you, I have some Midwest German ancestry, and they never act like their culture is unique to them and only them, because everyone is invited to their festivals. Italian-Americans typically welcome the rest of us with open arms, so most of us feel they have a culture of warmth and conviviality. I have been told that people in Québec are often very nice, too. As always, your article was enjoyable to read!

Melody Desjardins

Salut, Rebecca! I’m so glad to hear you enjoyed the post! I definitely agree about becoming a more inviting culture and I believe a lot of that has to do with becoming more of a public presence. There are many amazing and inviting people in the Franco-American community for sure, but I think we have to utilize the mainstream American culture by entering it in similar ways as the other cultures stated with festivals and fresh, new symbols alongside our fleur-de-lys! Thank you again for your comment!

Angela Chenus

I love your take on this whole question. I am the mother trying to hold on to language and culture for my first-generation Franco-Americans. My kids are you, after a fashion, they grew up mostly in the Midwest. You give me hope that there is interest in what I hold dear; knowing from where and whom they came on both sides of the family tree (and ocean, in our case, since it was France and not Quebec.) I would love to connect, my blog may not appear below (Blogger will not always speak to WordPress), but it is http://www.ahomeschoolstory.com. Drop me a line, merci!

Melody Desjardins

Salut, Angela! Thank you for your comment! I’m glad to hear that you are also passionate about the Franco-American story and I hope that your passion inspires your kids. We can reconnect with so much that was lost over decades and I believe part of that is reestablishing ourselves in the public eye with our beloved fleur-de-lys and fresh, new symbols for every Franco-American story. I’ll check out your blog, merci!

Dan Gaulin

Fantastic post, this is a topic that I have been thinking about for a few years but with nowhere near the clarity of your piece.

All of the elements that you describe: music, clothing, food, drink, traditional parties are part of the answer. I’ve noticed progress on all of these fronts including Poutine Fest which combines food and St Jean-Baptiste.

Another element is to continue to tell the story – to ourselves and to others. Americans, in general, do not have much of an idea of Canadian history and even less of French-Canadian history (I’ve learned more in the last 5 years than the previous 55!) It is an epic story with all of good, bad and ugly of colonialism. Even if you just concentrated on those stories that intersected with the American story the list is impressive: the horror of the Acadian removal; three wars (French and Indian, Revolutionary, 1812); Lewis and Clark; the migration to New England and New York providing the labor enabling the Industrial Revolution (and the anti-immigrant backlash including eugenics and the Klan); borderland topics such as prohibition & smuggling and the forestry industry.

Joe Gadbois

Excellent article. I might suggest your readers visit the Museum of Work and Culture in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. It tells succinctly the story of the Franco-American experience from Quebec farm to New England factory, parochial education, tenement life, and much more. Also, Assumption University in Worcester, Massachusetts, has The Mallet Collection in the d’Alzon Library that features an excellent website highlighting an impressive repository of Franco-American history . David Vermette’s book “A Distinct Alien Race” is an eye-opening work of historical research. Also, if one wants a rousing Franco-American anthem, look to the Maine singing group Schooner Faire’s “Quebecois” that will fill all Franco hearts with pride.

Melody Desjardins

Salut, Joe! Thank you for your comment! Definitely, the Museum of Work and Culture is on my “must-check-out” Franco list. Franco-American culture and history are alive and well; we just have to know where to look! My hope for the future is that we become more of a public presence and share our culture with more people.

Melody Desjardins

Salut, Dan! Merci for your comment, I’m glad you enjoyed the post! Agreed: I love PoutineFest and I look forward to SJB this year. And yes, retelling our story is so important to prevent our history and culture from becoming lost even more. But I am hopeful that with new discussions and ideas, we can reestablish ourselves and become a more public culture in the future.

John Bald

“Often, our invitation is a question of whether we speak French or not. If we only speak English, we are told that we cannot understand ourselves and are doomed to die out.” Oh man, you perfectly describe our experience. To me, the whole proposition of enjoying our own Franco culture was always presented that way. And since I hadn’t learned French, I always felt locked out, so to speak. Thanks for this rich, interesting blog post. The shuttle and the bobbin, yes! My mother & father worked in the Biddeford mills as teenagers. And I’d like to suggest another area of Quebecois/Franco culture: farming. My father had a “regular” job, but in his free time he had a 2-acre garden. His love and devotion to the land and it’s harvest was close to religious zeal.

Melody Desjardins

Salut, John! Thank you for your comment! I can relate to not speaking French: my Franco side was fluent, but as the generations went on, speaking French was unfortunately seen as an “invaluable” skill. All I had growing up was a few French words that were a part of my family’s regular vocabulary, but I’m working every day to learn French. So it’s possible, but it should never make anyone feel “locked out,” as you described. We should come together as Franco-Americans, whether we speak English, French, (or both!), and we can primarily connect through culture. Good point about farming! There are many Franco-American stories out there and the shuttles, bobbins, and spindles only cover some of those stories. I hope this post inspires Franco-Americans to find symbols within their own stories.

Nick Paquette

Excellent article Melody, you tackled a hard question – but it’s never too late, let’s start now!

When it comes to symbols, I take ideas from the celebration of all things Bavarian, Munich’s Oktoberfest. With Bavarian symbols, you see the flag and it’s colors, the pretzel, the beer stein (glas krug), the horn (oom-pah music), the lederhosen/dirndl, and the Tyrolean hat.

The colors of the Bavarian flag (blue and white) are a source of pride and are everywhere in Munich/Bavaria: arrangements of flowerbeds, checkered shirts, even frosting on gingerbread hearts. Whenever I see a BMW car, I see the Bavarian flag in the logo.

If I were hosting a Franco-American “Oktoberfest” or mentioning objects to add to the Millyard Museum, the first thing I see common with most groups under the Franco-American umbrella is the fleur-de-lis, our shamrock.

The maple leaf is as strong a symbol of our Canadian history as it comes: Quebec makes 70% of the worlds syrup!

We have our flag which is a combination of the stars and stripes/bleu-blanc-rouge with the fleur-de-lis.

The fiddle with wooden-spoons are common French Canadian musical instruments, past and present.

For clothing anyone can tie on – we have the ceinture fléchée (we should have seasonal ones we wear em year round!)

One symbol we don’t have is an official beverage/glass to share with the world (think Irish stouts and Munich lagers)…unless we can include all of the vins de France, which then would be the wine glass! 🙂

Melody Desjardins

Salut, Nick! Merci for your comment! Great suggestion about Barvarian culture specifically. I have always loved how many German-Americans have made their own culture out of using those cultural elements, even if their ancestors weren’t technically from Bavaria. I know the few German ancestors in my family tree that I’ve managed to find birthplaces for weren’t from the region, but I love German-American festivals! Agreed, the fleur-de-lys is definitely our top symbol and it could never be replaced. But I love how you listed all of these great symbols of German culture: they have their main symbol and then they have plenty of other great ones that are recognizable. That’s my intention with adding more symbols for Franco-Americans: I think we can do so much more to be recognizable. About the official Franco-American drink…maybe we can count maple syrup?? Hahaha.

Elizabeth Blood

I love the work you are doing, Melody! And agree we need more cultural traditions and symbols. I’m not sure about the mill tools, though. I feel like modern Francos are so far removed from those mill days. Most folks wouldn’t even know what a bobbin or a spindle is. That said, aside from tourtiere and poutine, I can’t think of any US Franco traditions or symbols that aren’t also either Quebecois symbols or Catholic traditions. So, I have no solutions to offer but appreciate your efforts to start the conversation!

Melody Desjardins

Salut, Elizabeth! Thanks so much for your comment! That’s fair: not all Franco-Americans will relate to mill tools, but I figured proposing the idea to those of us with mill ancestors could start up a conversation of adopting more cultural items over strictly religious items. Great hearing from you!

Kate Harrington

I love your take on this question Melody! It certainly is telling that the museum display case you cite held cultural artifacts of other nationalities, but none from the even more numerous French-Canadians who worked in the mills. While certainly music and food are recognizable symbols of Franco-America, it’s true that they are different than visual symbols. What’s interesting about your choice of the shuttle, bobbins, and spindles is that these are symbols from Franco-Americans’ reality here in the US, while leiderhosen, prayer shawls, etc. likely originated in those immigrants’ countries of origin. It doesn’t make them any less appropriate, of course. Something like the ceinture flechee from Quebec might be a traditional cultural symbol for some Quebecois, but probably would not have any relevance for any Franco-Americans today.

Melody Desjardins

Salut, Kate! Thanks for your thoughts! I agree about the ceinture flechee being a symbol, so it’s interesting how something like that wasn’t in this display case (or even a toque!). With symbols of Franco-America, I think there’s definitely inspiration to get from Quebec but I also believe in establishing some symbols for ourselves to differentiate us from French-Canadians and Quebecois. Of course, this was written primarily for Franco-Americans with mill ancestors in mind, so I think it’s up to us to add various items to reflect our own Franco-American family history and story. Great seeing your comment!