The legendary tale of Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie, published in 1847, told the tragedy of the Expulsion of the Acadians through the brokenhearted Evangeline separated from her fiancé, Gabriel. Written as a poem, the story tells of her perseverance to reunite with Gabriel against all odds. She searches for him as far as she can go, picking up clues to his whereabouts along the way.

Even with another man asking her to marry him instead of the missing Gabriel, Evangeline remains faithful to her fiancé. The tale of Evangeline reignited a sense of pride in Acadians, where she is forever a symbol of their undying spirit.

La Sagouine started as a radio show about an older Acadian woman recounting her life and talking about the history and tragedy of Acadie. The unnamed character came to life when the show became a play, bringing in the representation of an older woman to the stage and becoming an icon of Acadie.

Compared to female characters in Western literature of the 19th century, Evangeline was portrayed much more positively. Meanwhile, La Sagouine has been a hit as a one-woman show for decades. This lively character has brought the often forgotten stories of older women front and center of the Acadian story.

We’ll uncover these well-rounded characters in both of these stories where Acadians have found inspiration, symbolism, and folklore. Not only to confide together about their history but to celebrate their strong sense of pride and community.

A Young Acadian Woman’s Story of Perseverance and Love

The Acadian tale of Evangeline was written by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He tells the story of a young woman who experiences the Expulsion of the Acadians by the British in 1755.

The poem is written in an unrhymed dactylic hexameter, much like Greek and Latin classical epic poetry. Longfellow believed this was the best structure for the story, having been inspired by other literature.

In the written work, Evangeline becomes the personification of the Acadian struggle when so much was lost with families forever separated by their forceful removal from their land throughout the Maritime Provinces. The separation of Evangeline from her fiancé, Gabriel, represents the personal tragedies of the Acadians as a whole. Yet, through those tragedies, Evangeline herself became a figure of hope.

Throughout the story, Evangeline is firm in her mission to be reunited with Gabriel. Despite being given a chance to end up with her suitor, Baptiste, she never turns away from her love for her fiancé. And although she is knocked down by her circumstances, she clings to the hope of happiness in faraway lands with Gabriel.

Although her personal tribulations were fictional, Evangeline became a symbol enshrined in statues to honor her story of virtue in a corrupt world. Acadians can relate to her story with their own family’s long-lost history and tragedy.

The poem was inspired by a story first pitched to novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne from H. L. Conolly. A parishioner at his church referred to as Mrs. Haliburton told him the account of a young Acadian woman separated from her fiancé during the Expulsion but never gave up on finding him. Longfellow was so moved by the young woman’s dedication and undying love, he told the men that he would write the story.

It is the best illustration of faithfulness and constancy of women that I have ever heard of or read.

Longfellow (remarking his work on evangeline)

When the story was picked up by Longfellow, he had initially called the leading lady “Gabrielle.”

Longfellow was considering other names in a journal entry on December 7, 1845: “I know not what name to give to 𑁋 not my new baby, but my new poem. Shall it be ‘Gabrielle’, or ‘Celestine’, or ‘Evangeline’?”

By January 8, 1846, Longfellow called his poem Evangeline, where he wrote, “Striving, but alas how vainly to work upon Evangeline.”

In 1847, Longfellow published “Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie.”

Ye who believe in affection that hopes, and endures, and is patient,

Ye who believe in the beauty and strength of woman’s devotion,

List to the mournful tradition still sung by the pines of the forest;

List to a Tale of Love in Acadie, home of the happy.

Evangeline: a tale of acadie, prologue

The figure of Evangeline has taken on several symbolic representations, most notably in Nova Scotia and the United States. From statues, retellings of the tale, and giving nature significant meaning, Evangeline has gone beyond the passages of the original work to become artistic visuals of her character in physical form.

One statue of Evangeline stands in Grand-Pré National Historic Site in Nova Scotia. Based on earlier designs by his father Louis-Philippe Hébert, Québécois artist Henri Hébert sculpted the statue of Evangeline. She stands in front of the Memorial Church, longingly looking back at Acadie.

Although fictional, how she was written as the heroine of the story during the 19th century was defiant of the early stereotypes of women in most Western literature. These representations are outlined in “Western Women And True Womanhood Culture And Symbol In History And Literature” by June O. Underwood, who has written extensively on the subject of American frontier women.

In comparing the tale of Evangeline to women found in other forms of Western literature, especially with the examples of frontier women, these stories portrayed traits such as domesticity and submissiveness as inevitable. They were stereotyped through the male-dominated literature as fearful of uninhabited nature, forever a victim, helpful side mate, boisterous fanatic, or a lusty fantasy.

…the Plains exerted a peculiarly appalling effect on women….The wind alone drove some to the verge of insanity and caused others to migrate.

Walter Prescott Webb, in his 1931 classic, The Great plains

Meanwhile, in Longfellow’s Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie and the 1929 film Evangeline, the vast wilderness surrounding Evangeline is seen as beautiful. Nature embraces the characters in its lush fields and rolling hills, its massive landscape emphasized by the visual scale of these characters within its presence.

Even the dark, towering trees with their jagged outstretched branches are not menacing. Instead, they envelop Gabriel and Evangeline in protection as they walk through the forest and speak of their deep love for each other.

Over running water, my life I pledge to thee. My love shall never forsake thee…as long as water runs.

Gabriel and evangeline’s pledge before marriage, as seen in the 1929 film evangeline

In the story, Evangeline is not depicted as quiet or apprehensive. For the literature of the time, she could have been written as yet another “true woman.” This precedent has described women in literature as simultaneously “submissive, pure (sexually innocent or sexually faithful), pious, and domestic.”

These stories and standards originated from a male perspective, much like the rigid societal expectations experienced by the Franco-American Mill Girls and working mothers of New England in the 19th and 20th centuries.

American frontier women also had the idea of “True Womanhood” propped against them. These beliefs from male perspectives set their own standards to determine which women in society were worthy of their own natural-born title. Only women who remained domestic and submissive to men were regarded as “true women.”

…in traditional westerns, males are either frankly secular or pantheistic. Aside from occasional yearnings at sunset, or vague rumblings on the nature of God, religion is left to women. And, literarily speaking, when women get religious, it means trouble.

June o. Underwood, Western Women And True Womanhood Culture And Symbol In History And Literature, 1985

Despite these social pressures, Franco-American women working in the mills found opportunities to bond over their experiences as new working women. While they gathered during their breaks to eat together, play music, sing, or tell stories, the American frontier women gathered to build up the bare bones of their growing communities.

Women gather to create social and political change, which is why both groups of women from opposite ends of the United States found solace in their religion and relationships with each other.

Western literature, which prided individualism and self-reliance in its stories and male characters, viewed religion and community as unnecessary or threatening. Especially when frontier women became active outside of the church by getting political about the pressing issue of alcoholism and how to better protect children, home, and society from abuse.

Religious women in Western literature were written as fanatics who caused conflict, or even death and destruction, to the men around them. For example, in the 1924 novel Giants in the Earth, the wife of the main character is described as frail and cannot handle life out West. She becomes a cold, religious fanatic who eventually sends her husband to his death.

However, Longfellow writes Evangeline as innocent but not naïve as she wanders, searching for where Gabriel and his separated group ended up after the Expulsion. Her faith isn’t depicted as fanaticism but part of her Acadian heritage that guides her through the difficult journey. It also reminds Evangeline of the promise of marriage between her and Gabriel, giving her more reason to keep her hope of reuniting alive and finally seeing their struggle ending in union.

In the statues made to honor Evangeline’s character, her stance and posture read as solid yet graceful, with a look of confidence in her facial expression. Her eyes boldly focus on whoever looks her way. She doesn’t hold a cold stare, but her gentle smile beams a sense of hopefulness.

This version of the young Acadian woman marks the tomb of Emmeline Labiche, which is the name for Evangéline among Acadians in Louisiana. Dedicated on April 19, 1931, the statue in St. Martinsville, Louisiana, was donated by Dolores del Río, who starred as Evangeline in the 1929 film based on Longfellow’s story.

Dolores del Río’s portrayal of Evangeline was a woman of strong Catholic faith that carries her throughout the film. Her character is often portrayed as a wide-eyed innocent young woman, but the film doesn’t use this trait to exploit female innocence or set Evangeline up for the role of a helpless victim.

This part of the character’s personality is instead due to the tight-knit community of Grand-Pré. The residents are described in the poem and film as more innocent about their corner of the world.

Thus dwelt together in love these simple Acadian farmers,—

Longfellow, evangeline: a tale of acadie

Dwelt in the love of God and of man. Alike were they free from

Fear, that reigns with the tyrant, and envy, the vice of republics.

Neither locks had they to their doors, nor bars to their windows;

But their dwellings were open as day and the hearts of their owners; There the richest was poor, and the poorest lived in abundance.

Many portrayals of women written by men in the 19th century reflected the ideals of who women should be rather than who they actually were in reality. That’s what makes the portrayal of Evangeline unique from other male-written literature and their depictions of women at that time.

Longfellow wrote Evangeline as a well-rounded character with her own personality separate from Gabriel. Although the poem is about her search for him, Evangeline is the story’s heroine. Her account doesn’t end abruptly when Gabriel is nowhere to be found. Instead, she becomes a legend in Acadian folklore.

For American frontier women, devotion to God was put before devotion to man. The acculturation of women insisted on submission to men. But women’s piety, which they interpreted as the force to push their greater good in helping their communities, saved women from subjugation to human authority.

Evangeline’s faith in God kept her spirits high when she experienced devastating lows.

Near the end of the film, Evangeline reaches her breaking point when caught in a terrible storm. The wind whips and pushes her cloaked figure every which way, but she continues walking to find a way to safety. She stumbles and falls, shouts in agony, and cries in distress. When it seems all hope is lost, the flashes of lightning reveal a crucifix on a tree. Evangeline cowers underneath it and waits for the chaos around her to end.

During this storm, men don’t come to Evangeline’s rescue. Her faith in God gives her the sense of guidance and protection she needs to survive the night.

The theme of faith continues as the story closes with an older Evangeline as a Sister of Mercy. In the film, two men briefly speak about her being seen everywhere tending to the sick and dying. Even through her grief, Evangeline shares her nurturing abilities and holds strong to her faith.

Through the themes of Western literature depicting women of faith as fanatics, they have also been depicted as victims who cling to religion and are pitied for it.

However, Evangeline’s character as an older woman and a Sister of Mercy isn’t portrayed as tragic. Although the pain in her eyes that was captured so well by Dolores del Río tells a different story, Evangeline greets the sick with a smile and a comforting touch. She becomes a heroine to the downtrodden.

When an older Gabriel calls her over to his bed where he lays dying, Evangeline is fortunate to finally reunite with him. Her faith carried her through her entire life, as did her virtues of kindness and compassion, which she channeled into her strength.

God has been kind to let me find you at last.

Evangeline, 1929 film

The French Translation and Retellings of Evangeline

In 1865, French-Canadian author Pamphile LeMay translated Evangeline into French. But LeMay’s version isn’t a standard translation: his version went above and beyond in his reworking of the poem to make it rhyme. He also embellished certain sections and added more descriptions to flesh out the story further. It was his work that was noticed among Acadians and how they became acquainted with the story of Evangeline.

One of the first retellings of the story was by Sidonie de la Houssaye, a woman of Louisiana Creole heritage, who rewrote the story in her 1888 novel, Pouponne et Balthazar. In her version of the story, which she claimed was a family legend handed down by her grandmother, the role of Evangéline is Pouponne and Gabriel is Balthazar.

The name comes from the most well-known retelling written by Felix Voorhies, a district judge and member of the Louisiana House of Representatives, in his novel Acadian Reminiscences: The True Story of Evangéline. In his version, Evangeline’s role is written as Emmeline, and Gabriel is written as Louis.

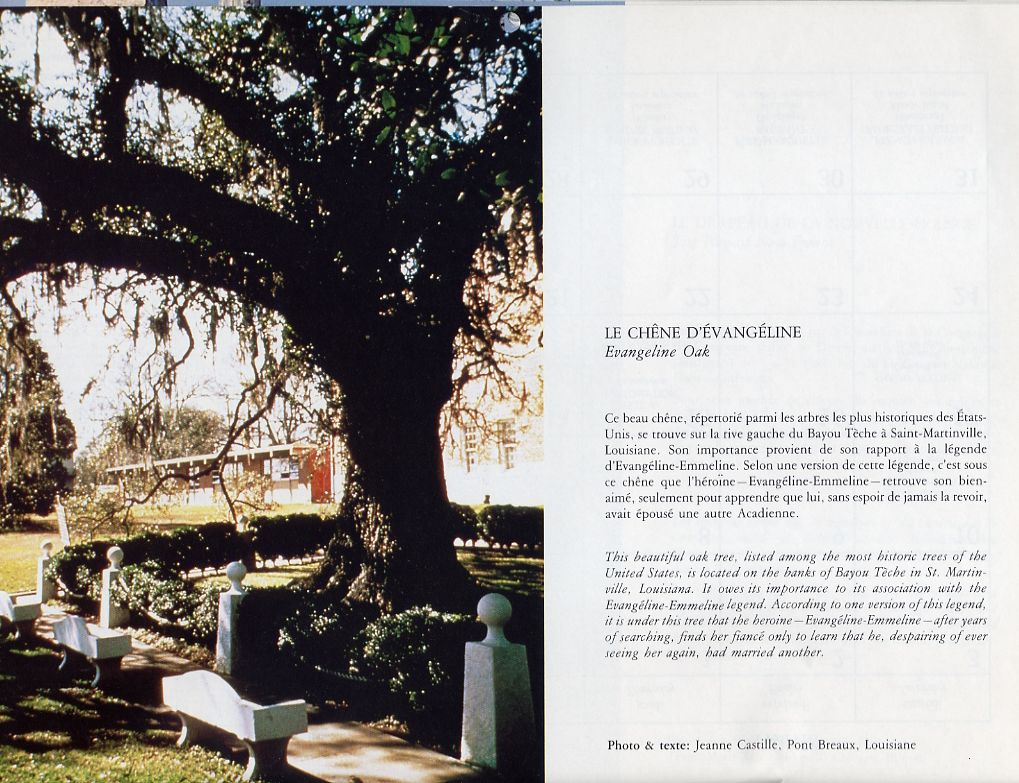

Le Chêne D’Évangéline, the Evangéline Oak, holds another retelling on the banks of Bayou Teche in St. Martinsville. Evangéline (or Emmeline) finds her fiance underneath the oak tree after years of searching in this version of the story. However, she finds that he married another woman, as he was sure that he would never see Evangéline ever again.

The story of Evangeline made the tragedy of the Expulsion of the Acadians known to North American readers. And, at the same time, it reignited pride in Acadians for their cultural perseverance and “the land of Evangeline.”

So why does Evangeline stand as a primary representation for the Acadians? How did her story inspire multiple retellings? While she was based on the experience of a real woman, Longfellow’s story of Evangeline deeply resonated with Acadians: her personal struggle of separation became their story.

She tells the stories of family separation, women separated from their children, and wives and husbands sent away in opposite directions. Evangéline is a remembrance for the lives disrupted and lost. From her perspective, we see this tragedy through a more sentimental lens as she is relentless in piecing her broken life back together with Gabriel.

An Older Acadian Woman’s Story on the Stage

Another female face of Acadie is an older woman in the play La Sagouine, written by Acadian author Antonine Maillet. Maillet’s works are a dominant force in Acadian literature, telling the stories and history of the Acadians through her cast of characters. Published in 1971, Maillet’s 16 monologues for La Sagouine were inspired by a real-life woman named Sarah Cormier.

The story was originally written for radio, where Maillet would read the monologues of her character. But after its first performance at the Dominion Drama Festival in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, the Théâtre du Rideau Vert in Montréal, Québec picked it up for a single performance in October 1972. From there, the play’s popularity flourished with audiences and more performances.

La Sagouine is the story of an older Acadian woman who works as a housecleaner. Throughout the one-woman play, the character monologues about her life, ranging from personal stories to gossip to what it means to have Acadian heritage. As she reflects on her own life, she also tells the story of Acadie and the Expulsion. The title is a derogatory term, translating to “the filthy woman” due to her job. However, it could also be a suggestive play-on-words of this unexpectedly mouthy and brash older woman.

Viola Léger has been the only actress to play the role of the unnamed Acadian woman, which she played over 2,000 times. Director Eugène Gallant spoke highly of Léger’s performance, stating that she mastered the texts and delivered them so naturally. Léger was very interactive with the audience, but not only with the dialogue. She spent the first performances walking among the incoming audience before the play began. When Léger started to monologue, audience members would recognize the lines they had heard on the radio. They instantly knew she was the lively, old Acadian woman telling her story.

Although Léger hasn’t played the character since 2017 due to health issues in her older age, she is happy that there are plans to find a new La Sagouine. The play turned 50 years old in July 2021, so it’s bound for a return.

But for now, the Acadian story and culture are played out at a park called Le Pays de la Sagouine, which opened to visitors in Bouctouche, New Brunswick, in 1992. Inspired by La Sagouine, actors and actresses in costume entertain guests with their own Acadian characters.

The park continues to teach visitors about the Acadians, from the music to dances to the history. More than 68,000 people visit the park every year, which far exceeds the small population of Bouctouche.

La Sagouine was a hit with Acadians in telling their story through the eyes of an older woman, which continues to be a rare perspective to this day. In storytelling and other forms of media, the stories of younger women are told more often. This makes the character of the older Acadian woman a much-needed perspective in hearing a variety of women’s voices in the community.

Through artistic expression, statues, written work, and the theatre, the history and stories of Acadian women have reached a wider audience to share women’s experiences.

Evangeline and La Sagouine became strongholds of the Acadian story because they offered a different and often unheard perspective. Although the personal accounts of these characters are fictional, they offer a view of how the historical tragedy of the Expulsion affected them as women.

It’s important to hear these stories, whether historical fiction or real-life accounts because women have a role in creating the culture passed down to their children. With a tragedy like the Expulsion of the Acadians, these perspectives can offer inspiration and hope to strike back against the devastation carried by generations of Acadian families.

In the document “On Seeing and Not Seeing,” historian Anne Firor Scott described the invisibility of American frontier women’s history as a problem of perception.

“It is a truism…that people see most easily things they are prepared to see and overlook those they do not expect to encounter.”

historian ann firor scott, On seeing and not seeing

Scott describes this perception as the reasoning behind the historical invisibility of frontier women’s political and social action. Because they had rigid standards of domesticity and submissiveness thrust upon them, Western literature reflected how women were viewed. And so, the dominant messages of the time buried the real hard-fought battles that frontier women gathered together for to make a change.

Which makes Evangeline and La Sagouine all the more significant. These accounts centered on the Acadian story demonstrate that these female characters were brought to the forefront when the unexpected angle was told.

Perhaps with the Expulsion, people who relate to the history expect the tragedy. The historical explanation is crucial to understanding the past, but it is limited by fact-by-fact retelling. Whereas the role these female characters played in the Acadian story brought sensitivity to break through the matter-of-fact barrier. Acadians had stories that they could resonate with on a deeper level, especially through the unique representation brought forth by Evangeline and La Sagouine.

Rather than overlooking the young woman searching for her lost fiancé or the wise-cracking older woman recounting her life story, they found themselves drawn to these eloquently told perspectives.

Rebecca D.

Thank you for this uplifting article! It is nice to note the positive aspects of Acadia’s challenging story, and I never thought about the poem from this point of view. Merci!

Melody Desjardins

Bonjour, Rebecca! I’m so glad to hear that you enjoyed this article.

Rhea Cote Robbins

Here is a classroom resource I developed while participating as one of thirty teachers from Maine and Massachusetts who participated in an intensive two-year (2003-2004) study of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s life and poetry that was organized by the Maine Humanities Council.

https://www.hwlongfellow.org/teachers_overview.shtml

=================

Longfellow Studies: The Acadian Diaspora – Reading “Evangeline” as a Feminist and Metaphoric Text

Evangeline in the Snow

Intended Outcomes:

Reading “Evangeline” as a feminist and metaphoric text.

Author: Rhea Cote Robbins, University of Maine, Penobscot County

Year created: 2005

Suggested Grade Levels: 6-8, 9-12

Content Areas and Strands:

English Language Arts — Reading

Social Studies — History

Duration: 10-15 days

Time Period:

1775-1850

Theme:

The People/Peopling of Maine

https://www.mainememory.net/lessons/longfellow-studies-the-acadian-diaspora-reading-evangeline-as-a-feminist-and-metaphoric-text/k9t4f6r6

Melody Desjardins

Merci, Rhea! I will check out your resources. I’ve been looking for more takes on the story of Evangeline.