During the 19th and 20th centuries, the Industrial Revolution in New England opened the doors for women entering the workplace. Although, hiring these young women was done out of exploitation in the incredibly rough work environments of the mills.

Even so, French-Canadian immigrant women and their Franco-American daughters had never experienced the sense of liberation brought to them by working for their own income. To the women who had experienced rural life in Québec, the mill towns and cities of New England were booming with opportunities in comparison.

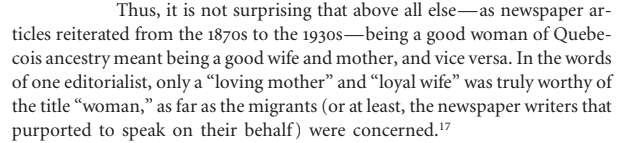

But these women, whether single or married, were often discouraged from becoming working women. The expectation of strictly staying at home was put on them by the teachings of the Catholic faith and male leaders in the French-Canadian and Franco-American community.

However, the many young and single “Mill Girls” had their own ideas of defining their womanhood through postponing marriage to gain what economic independence they could at that time. Whereas some married women wanted to bring in extra income when their husbands’ earnings weren’t enough to provide for their families.

Franco-American women were held to high purity standards and expected to practice the “True Womanhood” of French-Canadian women in the homeland of Québec. They were to avoid becoming Americanized at all costs. There were several rules in this definition of womanhood provided by men and even promoted by other women.

Most Franco-American women believed in having an identity in marriage and motherhood in their futures, but postponing these set expectations was seen as rebellious and sacrilegious. Nevertheless, with job opportunities open to them in New England, many of these women changed set expectations when they found independence they had never experienced before.

The Mill Girls of New England

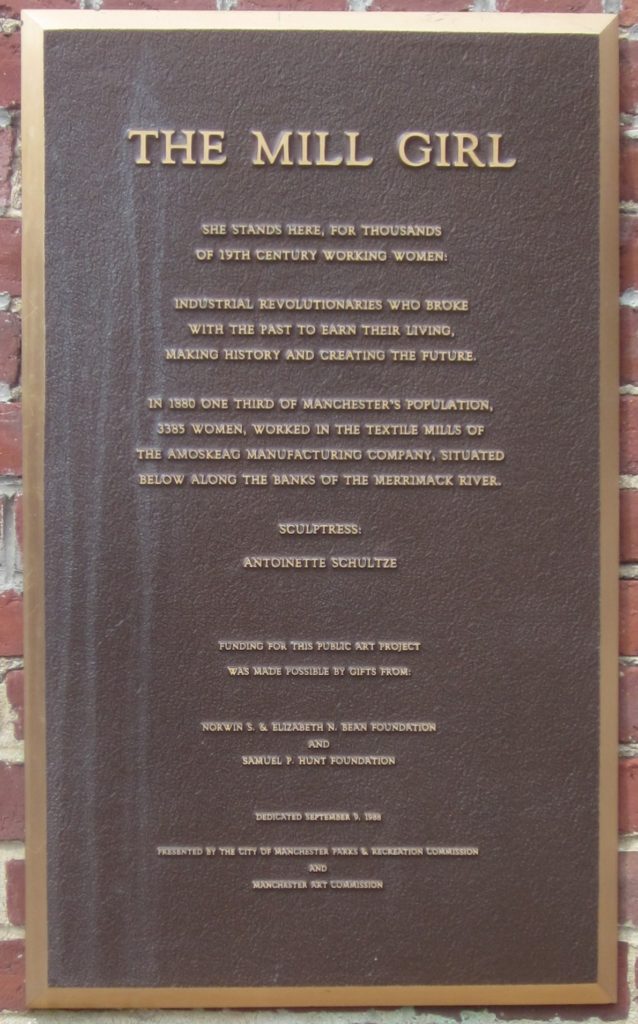

In Manchester, New Hampshire, a statue of the Mill Girl stands in the Historic Millyard District. Dedicated on September 9, 1988, she embodies the young girls and women who worked for the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, which produced cotton and wool textiles.

Sculpted by Antoinette Prien Schultze, she represents the “Mill Girls” who broke social norms to earn their own income, which gave them more freedom over their lives before committing to Franco-American expectations.

Nicknamed “Millie,” the Mill Girl stands with her left arm halfway raised with her head turned to the side, looking into the past while standing with us in the present. The plaque on the building above Millie is a written tribute to the working women of the past:

She stands here, for thousands

Of 19th century working women:

Industrial revolutionaries who broke

With the past to earn their living

Making history and creating the future.

Women of the 19th and 20th centuries broke into textile factory work when they faced intense cultural pressure to reserve their lives for marriage and children. Although women often left their jobs to get married and embrace family life, having the chance to work at all was looked down upon in the Franco-American community. Even other women heavily criticized women working, writing to the French-Canadian newspapers to make their criticism known.

“For quite a little while now, the feminist movement has become the hobby-horse of a good number of our American sisters. What pathetic speeches haven’t they peddled, in special congresses, on women’s emancipation, the right to vote, and the whole long stream of so-called woman questions!“

Marguerite, female columnist in Worcester’s L’Opinion Publique in the late 1890s

Although the mills hired young, unmarried women and girls to exploit them for lower wages, having an income allowed them access to consumerism in their new surroundings. With shops catering to their desires to wear American fashions and jewelry, the Mill Girls could spend their hard-earned money on necessities or these material goods.

However, these young women received criticism about participating in consumer culture, or “American materialism,” referred to by the French-Canadian newspapers. Because these male editors were concerned about working women ruining motherhood, they wrote about the creation of “Society Girls.”

“The society girl is distinguished by her love of fashion [as well as] her pronounced taste for parties, strolls, visits, public outings, theaters, balls. . . . She doesn’t go to church, or if she does, it’s only to see and be seen. She knows how to dance [better than she knows] how to pray to God and keep house. . . . If she marries before mending her ways, ten to one she’ll be an even worse wife than she was a bad girl. . . . Boys who’d like to have a wife who is quarrelsome, fussy, wasteful, and inattentive to a mother’s duties can confidently choose a girl who dresses like a model, nearly like the sort described above.”

“La Fille mondaine,” Le Foyer Canadien, 25 March 1873

In 1882, a French-Canadian newspaper editor in Lewiston, Maine, wrote an article directed at career women. He wrote, “We respect the wife, we revere the mother, but we confess we have but little esteem for [professional women].”

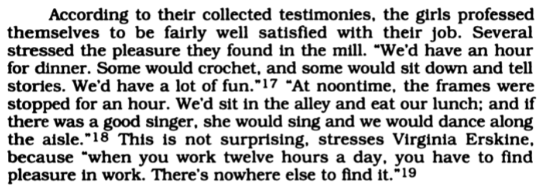

Meanwhile, the Mill Girls dominated the spinning rooms of the textile mills. There’s no question that they contributed to the hard work that kept these mills running. These women usually lived with their families, but some lived together in dormitories close to the mills. For them, the city life was rough but liberating, providing opportunities to work with other women and form close bonds while also earning a wage.

The societal pressures of becoming a mother or strictly working are unique to women, even today. Having the opportunity to temporarily leave the home to work in the mills would have been worth it for the extra income. But having the chance to form connections with other women is valuable in its own way.

When we form friendships with other women, we navigate the social pressures put on us together. Finding solidarity in each other through the different paths we can take in life is beneficial to our well-being. These paths are unique to us, from becoming mothers, continuing to work, or doing both while still getting heavy praise and harsh criticism.

Young girls and women were 78% of the mill workforce, yet were often blamed for tension in the Franco-American community if they went against “natural law.” A society of working women threatened the continuation of French-Canadian ideals of motherhood. Which was believed would affect the future of the Franco-American way of life.

Women were revered as the ones to pass on the religious and cultural traditions to their children, which many of them were willing to do at some point in their lives. But moving from the rural life in Québec to bustling American cities with the opportunity to have their own income, even for lower wages, gave them freedom and choice they hadn’t experienced before.

These Franco-American Mill Girls fought through rigid expectations of financial dependence to gain their position in the workplace, even temporarily. They worked in dangerous conditions in hot, dusty rooms with loud machinery for less pay. They faced constant scrutiny in the French-Canadian press by male columnists defining womanhood for themselves, as well as harsh criticism from other women who believed in these rigid standards.

Their actions and determination to hold down a dangerous and demanding job were motivated by their desire for independence. In doing so, they challenged the strict cultural norms of their time and showed that they were capable in a culture that only viewed them as having “virtue, good morals, and influence” once they became wives and mothers.

The Mill Girls proved their worth in being hard workers and creating a community of Franco-American women who found solidarity in each other through their daily challenges.

The Franco-American Wife, Mother, and Mill Worker

The married women who worked and raised a family often had more criticism against them than the Mill Girls. The income they brought in (oftentimes with their children) contributed to the family’s savings alongside the husband’s income as the breadwinner. Some families planned to return to Québec, so women participated in earning extra income for this goal.

La Dame de Notre Renaissance Française represents the French-Canadian immigrants who settled in Nashua, New Hampshire, during the early 20th century. Dedicated on May 19, 2001, the statue honors the women and children who worked in the mills. La Dame wears a cross around her neck with a spindle in the pocket of her dress. Her young son is by her side, holding a French-language book. They stand together in Le Parc de Notre Renaissance Française along the Nashua River.

The park and statue of La Dame remind Nashua’s Franco-American community of the contributions of the French-Canadian immigrants who came before us. The statue was sculpted by Christopher R. Gowell, who stated that she was “extremely proud to have had the opportunity to sculpt a figure of a strong French-Canadian woman.”

But the French-Canadian press heavily criticized married women working in the mills. The men writing the majority of articles claimed the only role women needed to fill was wife, mother, and homemaker. To be anything more was becoming Americanized. The “True Womanhood” of the Franco-American woman was to follow the Catholic church, get married, have children, and remain at home.

Women were not choosing to work to rival men; they worked to earn extra income for themselves or their families to provide.

Although many women chose to be wives and mothers, some of them also wanted their own income for their own needs. These included buying premade American products, from food to clothing, that saved them valuable time during their homemaking.

Wives and mothers turning to these ready-made products and aspiring to have an income received criticism from the male-run French-Canadian newspapers. Their idealized role for these Franco-American women also included avoiding any modern conveniences. Anything that did not reflect the rural life back in Québec was considered Americanization.

The intense fear of women’s suffrage ruining the family dynamic didn’t consider the crucial, non-stop work that married women already shouldered.

This isn’t to say that being a wife and mother is a breeze or oppressive. Women who chose home life described it as liberating by not having the expectation to work. They may have not broken societal expectations at that time, but their work in the home was necessary regardless. The issue with criticism of women who chose to work was the expectation that they should be financially dependent on their husbands without a choice.

Some men abandoned their families, leaving their wives to either pick up millwork or desperately write to the newspapers asking their husbands to return home to help them and their children survive. Many Franco-American women took their husbands to court if they didn’t bring in enough income to fulfill their breadwinner role, which negatively affected how men saw their expected role of making enough income to provide. Even in marriage, women were supposed to feel secure on their husband’s income, but abandonment or low income would burden the family.

However, the newspaper editors felt sympathetic towards the wives when their husbands left them, blaming the men for not fulfilling their breadwinner role. But male leaders in the Catholic church would only approve of married women working under those circumstances. One leader stated, “Married women should not be allowed to work in the mills except in cases of extreme need.”

These measures dictated their individual choice of wanting to work when Franco-American wives and mothers played an essential role in the community as caretakers. They learned how to balance finances with a low income. They spent their time caring for others, even taking on the role of nurses for the community in housing areas that were often overcrowded and unsanitary. Far from being “Society Girls,” these women cut expenses and mended their children’s clothing instead of buying new items.

In the life of the married Franco-American woman, taking up work to help the family took mental and physical toughness on top of being the primary caretaker. Operating machinery and working up to 12 hours a day may not have been the ideal environment for women of this time. Still, they were willing to go above and beyond to contribute.

Sacrifices of the Franco-American Woman

My mémère, Cecile Desjardins, was born in 1919; one year before women won the right to vote in 1920, which coincided with an uptick of the articles in the French-Canadian press condemning working women.

When she was growing up, Cecile had to leave school to take care of her younger siblings during the Great Depression. She was only 14 years old when she became a caretaker while her mother and father worked during the day.

Having only received an 8th-grade education, Cecile wanted to attend high school and college to get back what she had missed. But she was told that higher education was not an option for her. As a young, Catholic, Franco-American woman, her only priority should be marriage and motherhood. Meanwhile, her older brothers could attend higher education and received support from the family to do so.

But she found work at Jackson Cotton Mills in Nashua with one of her sisters, where she would later recall hating the work in the hot, dusty rooms. Shortly before meeting her husband, she found work at Millers Department Store in Nashua, New Hampshire.

Being a devout Catholic, Cecile was never against marriage and motherhood, as this was the path she wanted to pursue. She only wanted to get her education back for herself before becoming a wife and mother. Even after years of balancing family and work, winning the right to vote, and gaining more independence little by little, some options remained closed for many women.

Although my mémère’s work would never lead into a career, she still sought work to gain some financial independence for herself. Even though she had to give up her dreams of higher education, she later fulfilled the role of wife and mother that she had intended.

Women’s Suffrage never “ruined the family” because this cultural role of women was still the expectation decades after 1920. Some women wanted to experience independence for themselves before committing to marriage.

Whether through holding a job or receiving higher education, they had to prove their worth and capabilities in desiring personal goals. As women, we are brought up to believe that the most significant impact we can have is what we bring to others rather than what we can accomplish ourselves.

For women of the past, sacrifices had to be made much more often. Cecile worked around the challenges, all while hoping for a better future for her children. Despite the setbacks, Cecile was proud of her Franco-American culture and cherished her Catholic faith. Speaking up about her desire to finish her education and pursuing work was another voice redefining what it meant to be a Franco-American woman.

She passed down what French she spoke to her daughters, although English was being spoken more and more by that time. She was the loving mother and loyal wife that fit the strict definition of womanhood that one male editorialist wrote in 1909, but she was so much more than these traditional roles in her husband’s and daughter’s lives.

Cecile earned the title “woman” before marriage and children. She became a woman out of the hardships she had to fight through as a young girl pulled out of school without the chance to return. She shouldered the difficulties of being a caretaker for her younger siblings at such a young age while their parents worked long hours. When her older brothers got to attend higher education and not her, she had to grin and bear her lost education for the rest of her life.

She found her womanhood in facing challenging circumstances unique to women and becoming stronger from those experiences while empowering her feminine traits. She was a natural at being a mother and enjoyed knitting, especially hats and mittens for her daughters. When she made enough for the family, she would knit more and give them away to other families in her community. Her best friend, a Franco-American woman born on the Québec border who made a new life in New England, would join her in giving knitted items to the soup kitchens.

She enjoyed her quiet time with crossword puzzles or a cigarette. Her warm and caring nature radiated, but she could get feisty if provoked. Although most of her French-Canadian dishes never satisfied her family’s appetite, she made the best Gorton. She embraced traditional roles in her way and not to the divine standards of her time.

There is only so much to be done to change cultural expectations, and my mémère’s Franco-American experience had to line up with strict expectations. But the women before her had no small part in paving the way for future generations, including her mother, who worked in a shoe shop.

Every item on the statue of La Dame de Notre Renaissance Française holds a piece of Franco-American womanhood. The cross she wears represents the faith of these women, even when its teachings were used against them to dictate their lives. Women like my mémère kept faith close to their hearts to give them strength and remind them of their compassion.

The French-language book in the hands of her son expresses the culture that Franco-American women actively passed down. Women were still the primary caregivers, whether full-time homemakers or splitting their time between home and work. They passed down the language and culture of their French-Canadian heritage to their children.

Her spindle in the pocket of her dress is a remembrance of the strenuous work some mothers chose. Even being exploited for lower wages didn’t prevent them from doing what was necessary to help their families. In doing so, this shifted the idea of the perceived French-Canadian woman with no economic power into life with opportunities of financial independence before settling into their identity as wives and mothers.

Even when we’ve lost so much of who we are, being Franco-American today can be credited to these women. They told their children stories in French and passed down much-loved traditional French-Canadian recipes. As well as instilling who they were as Franco-Americans in their new home.

Franco-American women, from the Mill Girls to the working wives and mothers, challenged the preconceived notions that their womanhood was only valid the moment they married and became mothers. They faced opposition to working in the mills and served as caretakers in the community, pursuing their greater good that they fought to define themselves.

Marc Collard

This is very well thought out and very well written. Thank you from French Canadian descendent from Biddeford, Maine. Having worked in the Pepperell Mill during two summers, I can appreciate they hard work mill workers performed.

D Spillman

Thank you for posting. I enjoyed reading the post. I hope you continue to make the contributions of French Canadians to the United States. So far the focus has been on New England. It is my hope that there focus will at some point include the mid west including French Canadian settlers who settled in Detroit, MI., Lafayette, IN., Vincennes, IN etc.

Melody Desjardins

Merci for your feedback! Yes, the focus has been on New England Franco-Americans but I’m working on expanding to Midwestern Franco-Americans. I’ll look into the specific cities you’ve listed, as well!

Jodi Perras

D. Spillman — You may enjoy my blog, leavesofmenominee.com, which is about my great-grandmother’s life in 1904 in Hermansville, Michigan, and the French-Canadian families in that area.

I always enjoy reading your posts, Melody!

Ron Héroux

Well written Mélody . Made me think of my mom who worked in the mills of Manchester, NH and Pawtucket, RI in the 20s and 30s. A heartfelt thank you for bringing back memories of my mom, Hélène (Bélisle) Héroux, born in Wotton, QC in 1905 and passed away in Central Falls, RI in 1994. She taught me how to be compassionate and how to treasure and preserve my maternal language, le Français, and to be proud of my Franco-American heritage.

Merci