As I continue the journey down the Franco-American rabbit hole, something I’ve become more interested in has been the traditional folk music and the modern interpretations of our history, language, and culture.

Although I can’t pick up on all of the French in the songs yet, the music itself is enjoyable to tap my foot to and let my mind wander into a folksy Franco-American story. I can’t dance to save my life but when the steady rhythm of the podorythmie and smooth melodies intertwine to create an upbeat sound, I can imagine dancing along in a room full of other people dancing to the same songs.

Yes, I’m a sucker for the Meryton Assembly dance scene in Pride and Prejudice. How would anyone guess? And obviously that other dance scene but that’s another story.

This traditional folksy-style music creates so much vibrant energy, even if you’re listening to it alone. So when I recently discovered that Franco-American music is an actual genre, I jumped right in and frantically searched for more.

I had already known of a few Franco-American artists, but I didn’t know that there were whole playlists out there with a variety of instrumental folk music and music with lyrics describing the Franco-American story.

So when I heard a few songs from a playlist of different artists, I had to dig for the origin of these songs. And that’s when I found the Mademoiselle, Voulez-Vous Danser?: Franco-American Music from the New England Borderlands album.

Recorded between 1994-98 at gatherings and songfests in New England, these songs tell our story in French, English, a combination of both in the same song, or the vibe of a song is all in the instrumental music.

There are stories touching on the immigration of the French-Canadians who settled in New England to work in the mills, the effect of the French language not being passed down, and personal stories of identity and becoming fully Americanized.

I listened to the entire album and pulled out my favorites, as well as a few songs from other playlists, to take a closer look at the lyrics and discover our story from the perspective of these musical artists.

Although not all of the songs listed are upbeat and positive tunes to dance to, they’re still an important part of the Franco-American story that should be told.

So let’s uncover the lyrics and enjoy the music along the way!

French in America – Josée Vachon

I discovered Josée Vachon through the French-Canadian Legacy Podcast. As many of you probably know, French in America is the intro and outro music for each episode. So this was the first Franco-American song in the genre that I heard.

I found the podcast in 2019 and immediately searched for the song, needing to hear more than a snippet. And so, I listened to more of Josée’s songs. To this day, French in America really sticks out to me.

It’s so relatable to many of us born and raised in the United States who never learned French. For the most part, our upbringing was American. Besides growing up with a few French words or phrases, we spoke English as our first and only language.

The lines that really stand out to me are near the end of the song, when the lyrics go from French to English:

The borders between lands are not all that we have crossed

Now, we must be taught the language that our mothers lost.

Now our fathers look at us and sigh with despair

To think that everything they love we simply do not share.

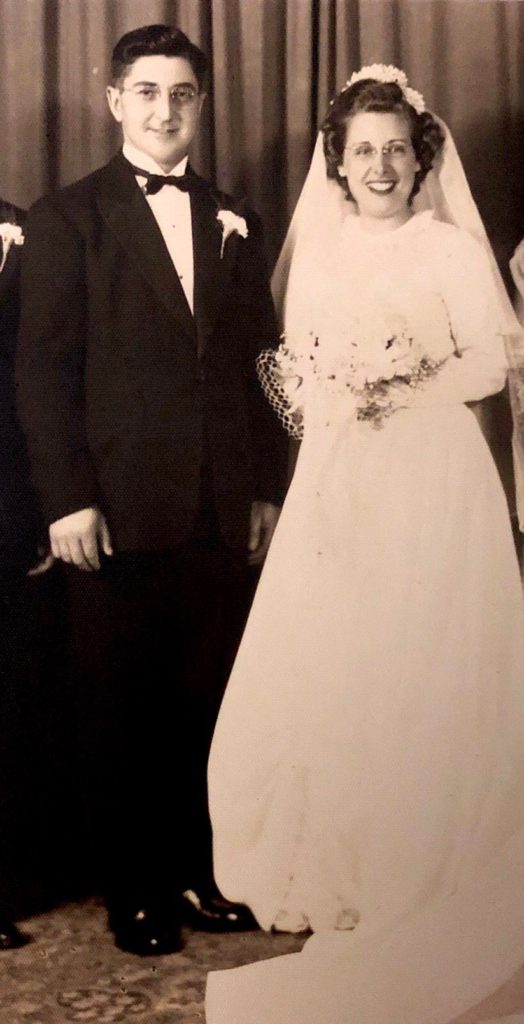

When I hear the line, “Now, we must be taught the language that our mothers lost” and “Now our fathers look at us and sigh with despair,” I think of my mémère and pépère.

Although they were both born and raised in Nashua, New Hampshire, their first language was French until they attended school and learned English. But even after learning English, they never abandoned speaking French.

Knowledge of the French language was important to them, especially to my pépère who felt it was a direct connection to his heritage and culture. In fact, he was a member of the Nashua Richelieu Club, where all meetings and discussions took place in French.

Which brings me to the last line, “To think that everything they love we simply do not share.”

I had tried to learn French many times before but I always became either too busy to continue, too intimidated by the process of learning a new language, or I didn’t have the best resources to properly learn.

For a while, I had given up on the idea and accepted that I would never learn to speak French. But I began noticing that my mind was starting to change the more involved I became in the Franco-American community.

The more I listened to that line, the more I wondered if my pépère would be disappointed that I didn’t care about speaking French. Even though he passed away one week after I was born, I feel like I know him like I knew my mémère.

That line rekindled the spark I had lost, but the memory of my mémère and pépère gave me the inspiration to commit in my journey of learning French. Which brings us to the previous line of the song, “Now, we must be taught the language that our mothers lost.”

Which is exactly what I’ve put into motion by taking in the resources to continue picking up the language that was dropped within only a few generations.

Entre Moi “Between Me” – Josée Vachon

Oui, Josée Vachon makes this list once again with her song Entre Moi, or Between Me. Although I love French in America, the cheerful but bittersweet tune to her story of feeling torn between Canada and the United States is catchy and so engaging.

The creative take on singing her name, Josée, to the tune of “Oh say can you see?” from the U.S. National Anthem solidifies the connection to both cultures that many Franco-Americans feel so strongly.

As the line goes,

Josée, qu’est-ce que tu fais pour survivre dans les Etats?

Josée, what are you doing to survive in the States?

The song plays out as if her cousins are writing to her, asking why she stays in the U.S. when her family in Canada misses her and wants her back in the country of her birth. And Josée’s answers to their questions are that she loves both countries and cannot choose between them:

Ces deux pays, je dois choisir entre eux. Veuillez bien m’écouter, je les aime bien tous les deux…

These two countries, I must choose between them. Would you please listen to me, I like them both…

Because most of our ancestors came to the U.S. during the early 20th century, those of us in the Generation X and Millennial age range most likely heard some French being spoken by older family members.

We picked up words and phrases in French and only thought of ourselves as Americans. Until we shared terms like mémère and pépère, bureau and barrette, gorton and creton with our friends or peers who had no idea what we were saying, we picked up that these weren’t generic American words.

They were unique to us and we didn’t even know what to do with them after being corrected with the English alternative.

Growing up in the Midwest, I can’t tell you how many times I would say “bureau” only to have someone pipe in with, “Don’t you mean dresser?”

Telling my friends that my mom bought me new barrettes and being corrected with, “Those are called hair clips.”

Coming back from a summer trip in New Hampshire and telling my friends that I tried gorton, being met with confused looks, “Oh, I thought you said goat tongue!”

Or who is this “Mémère” I keep talking about? Why not say “Grandma?”

I’ll never deny my American nationality, but I also cannot deny my French-Canadian descent. Because I never allowed anyone to correct my French terms, the culture managed to hold onto me by a thread. Why would I call anything a different word than what I already know it as in French?

Which brings us to the last line of that segment of the song,

Mais comme je suis ici, et que je m’identifie, Je n’suis plus Canadienne, mais Franco-Américaine.

But since I am here and I know my identity, I am no longer Canadian, but Franco-American.

Even if we aren’t Canadians by birth, as Franco-Americans we carry that piece of Québec with us that our great-grandparents brought over with them to the U.S.

Just as this line in the song goes, we can finally accept that we don’t have to choose between anything: we can be both and still embrace the old culture given to us, even if it was barely hanging on.

J’entends Le Moulin

J’entends Le Moulin is a folk song from Québec that translates into I Hear The Mill, but I’ve found other versions of the song under the name “I Hear The Wind Mill” or “I Hear The Mill Wheel.”

The song has the steady, rhythmic beat of “ticka-tacka,” meant to replicate the sound of the mill wheel in a factory. Although I couldn’t uncover whether this was directly related to the mills of New England, it can still describe the Franco-American story.

I hear the mill wheel, tick-a-tick-a tock-a, I hear the mill wheel turning

I hear the mill wheel, tick-a-tick-a tock-a, I hear the mill wheel turning

Tick tick-a tock-a tick tick tock Tick-a tock-a tick-a I hear the mill wheel,

Tick-a tick-a tock-a, I hear the mill wheel turning

This could easily be a song about our ancestors working the endless hours in the mills to make a living. While listening to this song, I picked up imagery of men, women, and children keeping up with the rhythm of their job as the sounds of the mills become repetitive, keeping them on track.

As the song gets faster, the tune becomes upbeat. Which sounds strange about a song describing the work in the mills and the sound it produces.

You would think a song about working back in those days would sound miserable. But this is one that I would get up and happily dance to as if it could be an acknowledgment of the difficult work our ancestors endured. As well as a “merci beaucoup” for withstanding the harsh life they experienced.

This concept of repetitive sounds ties into this next song about a French-Canadian family moving to New Hampshire to work in the mills.

The Shuttle – Chanterelle

This song opens with the steady rhythm of foot-tapping that is kept up until the end. With the fiddle playing in the background, this tune is energetic and could be upbeat. But the lyrics have a much different story to tell.

It starts with the common story of French-Canadians leaving Québec for New England. Although they found work in the mills, it was a dangerous job with unbelievably long hours. As the song highlights, entire families would sometimes be working in these mills.

We left our home in St. Hubert to work the Amoskeag

In Manchester, New Hampshire, in 1883.

Six days a week we rise at four to work our sixteen hours.

Ma mère and me are spinners inside their tall brick towers;

Mon père, he’s in the weaving room; mes frères, they sweep the floor.

We see them, but we cannot speak above the shuttle’s roar.

I think the tick-a-tick-a tock-a rhythm from J’entends Le Moulin could fit into this song, as both stories talk about hearing a repetitive sound within the mills. But this song takes a darker turn in the lyrics and the tune.

The people who worked there must have had moments of mental unstableness from tedious work that they had to do to survive. Not to mention the physical toll these jobs put them through.

These next lines talk about the “thumping mills,” another indicator that this sound is going and going all day long as they work. With the line right after, the main character of this story is questioning how to remain mentally stable in such an unsettling environment.

Of health and youth spent quickly in thumping mills of brick and tin;

How do we keep our sanity in the shuttle’s hellish din?

The song ends with the narrator presumably writing to her relatives back home, or wishing she could tell them not to come to the New England mills for work. In this hopeful attempt to save them from the fate her family found themselves in, she describes “recruiters” tricking people into leaving Québec with a free train ticket south.

At the end of the song, our narrator leaves us with her final warning from the mills.

Oh, my friends and family in lovely St. Hubert,

Don’t listen to recruiters when they ask to pay your fare.

Stay at home, don’t listen to their blandishments and lies,

Or you’ll end up, a slave like me to the shuttle that never dies.

These songs that tell the harsh realities of the French-Canadians who left everything behind at a chance in the United States can leave us with a feeling of misery. It’s understandable, and in our lives today we can’t imagine how difficult it must have been.

I wanted to explore the Franco-American music genre to find positive and upbeat tunes that traditional folk music usually brings. As I said in the beginning, I love music with that folksy sound because it’s so cheery and energetic.

As I mostly listened to the Mademoiselle, Voulez-Vous Danser?: Franco-American Music from the New England Borderlands album, I discovered a balance of the positive and negative. It was like the happiness for Franco-Americans back in the mill days were momentary and so these songs reflect either only the good, only the bad, or a little bit of both.

But no matter the feeling, these songs guided me into an imaginative dance through every major high and depressive low of the Franco-American story.

Through the modern-day struggles of what to call ourselves to the endless work days those who came before us had to endure.

And through it all, I feel more connected to our story than ever before.

Annette

Melody, I can identify with your feelings and wanting to embrace your Franco-American heritage. I’m so thrilled that you are blogging about this and bringing so much enthusiasm and attention to our common family stories and the history we share. C’est merveilleux!

car insurance ontario by age

Great post.

Scott Graves

One of the most immediate ways of embracing our Franco-American heritage comes from making this music, from preparing the meals our Memere’s and Pepere’s did, the folkways that bring their experience back to us through time and space. My Pepere listened to this music and being he was from both sides of the border to a variety of American, or really North American popular music. In fact, one of our biggest cultural strengths is the gumbo that has simmered over centuries here in North America manifested in our music. When we speak of Jazz, those of us who make that music really speak about all the musical traditions we bring to the table, including those of us of Franco-American descent.

Sarah Chamberlain Reeds sarahjreeds2002@gmail.com

Very interesting, just learning my French heritage after 88 years of wondering, my great aunts who were Daughters of the King, family relocated to Kaskaskia Illinois, in mid 1700s want to know so much more!